Unit 1 Information Needed

What is an enterprise?

The TOGA Standard considers an "enterprise" to be any collection of organisations that have common goals.

For example, an enterprise could be:

- A whole corporation or a division of a corporation

- A government agency or a single government department

- A chain of geographically distant organisations linked together by common ownership

- Groups of countries, governments, or governmental organisations (such as militaries) working together to create common or shareable deliverables or infrastructures

- Partnerships and alliances of businesses working together, such as a consortium or supply chain

The term "Enterprise" in the context of "Enterprise Architecture" can be applied to either an entire enterprise, encompassing all of its business activities and capabilities, information, and technology that make up the entire infrastructure and governance of the enterprise, or to one or more specific areas of interest within the enterprise. An enterprise may include partners, suppliers, and customers as well as internal business units. In all cases, the architecture crosses multiple systems, and multiple functional groups within the enterprise.

The enterprise operating model concept is useful to determine the nature and scope of the Enterprise Architecture within an organisation. Many organisations may comprise multiple enterprises, and may develop and maintain a number of independent Enterprise Architectures to address each one. These enterprises often have much in common with each other including processes, functions, and their information systems, and there is often great potential for wider gain in the use of a common architecture framework. For example, a common framework can provide a basis for the development of common building blocks and solutions, and a shareable Architecture Repository for the integration and re-use of business models, designs, information, and data.

Why is an Enterprise Architecture needed?

The purpose of Enterprise Architecture is to optimise across the enterprise the often fragmented legacy of processes (both manual and automated) into an integrated environment that is responsive to change and supportive of the deliver y of the business strategy.

The effective management and exploitation of information and Digital Transformation are key factors to business success, and indispensable means to achieving competitive advantage. An Enter prise Architecture addresses this need, by providing a strategic context for the evolution and reach of digital capability in response to the constantly changing needs of the business environment.

Furthermore, a good Enterprise Architecture enables you to achieve the right balance between business transformation and continuous operational efficiency. It allows individual business units to innovate safely in their pursuit of evolving business goals and competitive advantage. At the same time, the Enterprise Architecture enables the needs of the organisation to be met with an integrated strategy which permits the closest possible synergies across the enterprise and beyond.

And lastly, much of the global privacy legislation demands that processes around personal data are fully documented in a way that can be easily understood by untrained readers — such as the data subjects and judges and lawyers. The penalties for failing to have this can be very significant. Clearly the creation of this basic documentation arises from the changed fundamental considerations and this is now crucial.

Why is it Important to Develop an Enterprise Architecture?

An EA is developed for one very simple reason: to guide effective change.

All Enterprises are seeking to improve. Regardless of whether it is a public, private, or social Enterprise, there is a need for deliberate, effective change to improve. Improvement can be shareholder value or agility for a private Enterprise, mandate-based value proposition or efficiency for a public Enterprise, or simply an improvement of mission for a social Enterprise.

Guidance on effective change will take place during the activity to realise the approved EA. During implementation,1 EA is used by the stakeholders to govern change. The first part of governance is to direct change activity – align the change with the optimal path to realising the expected value. The second part of governance is to control the change activity – ensuring the change stays on the optimal path.

The scope of the improvement drives everything that is done. A methodology that serves to validate both the objective and the change, ensuring that both are feasible, delivers the desired

value, and in a cost-effective manner. An architected approach provides a rigorous planning and change governance methodology.

In its simplest terms, EA must describe the future state and the current state of the Enterprise. The description of the future state enables the right people to understand what must be done to meet the Enterprise’s goals, objective, mission, and vision in the context within which the Enterprise operates. The gap between the Enterprise’s current state and future state highlights what must change. A good EA facilitates effective governance, management, risk management, and exploitation opportunities. A list of gaps makes obvious what must change and the implications of that change: is the proposed project in alignment with what is needed? In alignment with priority? In alignment with the complete set of goals and objectives?

The preceding paragraphs highlight the conceptual scope of EA. This scope often leads to the assumption that EA is only used to answer the big questions. Nothing can be further from the truth. The same concepts, methods, techniques, and frameworks can readily be used to address the end state, preference trade-off, and value realization for big and little questions. The essential difference is not what you do; it is what the documented architecture looks like. The scope of the system varies; the detailed description of elements and properties vary. All of the concepts remain the same.

What is the Role of Enterprise Architecture?

Enterprise Architecture provides a framework for change, linked to both strategic direction and business value. It provides a sufficient view of the organization to manage complexity, support continuous change, and manage the risk of unanticipated consequences.

Enterprise Architecture is:

- A description of the elements within an organization, what they are meant to achieve, how they are arranged, how they perform in practice, and how they respond to change

- A framework (structure, approach, and process) for managing change to those elements and their arrangement; to continuously adapt to organizational change in line with strategy (goals and objectives) and circumstances (specific requirements)

- The practice of acting to manage and evolve the Enterprise Architecture at all levels of control, change, and pace

What are the benefits of an Enterprise Architecture?

- More effective strategic decision-making by C-Level executives and business leaders:

- Quick response to change and support for enterprise agility aligned with the organisation strategy

- Organisational transformation, adopting new trends in business and technology

- Organisational change to support Digital Transformation

- Organisational and operating model changes to improve efficiency and effectiveness

- More effective and efficient business operations:

- Lower business operation costs

- More agile organisation

- Business capabilities shared across the organisation

- Lower change management costs

- More flexible workforce

- Improved business productivity

- Improved organisation integration in support of mergers and acquisitions

- More effective and efficient Digital Transformation and operations:

- Extending effective reach of the enterprise (e.g., through digital capability)

- Bringing all components of the enterprise into a harmonised environment

- Lower development, deployment, operations, support, and maintenance costs

- Improved interoperability

- Improved system management

- Improved ability to address critical enterprise-wide issues (e.g., security)

- Easier upgrade and exchange of system components

- Better return on existing investment, reduced risk for future investment:

- Reduced complexity in the business and IT

- Maximized return on investment in existing business and IT

- The flexibility to make, buy, or outsource business and IT solutions

- Understanding how return on investment changes over time

- Faster, simpler, and cheaper procurement:

- Buying decisions are simpler, because the information governing procurement is readily available in a coherent plan

- The procurement process is faster - maximizing procurement speed and flexibility without sacrificing architectural coherence

- The ability to procure heterogeneous, multi-vendor open systems

- The ability to secure more economic capabilities

Characteristics of EA

The World-Class Enterprise Architecture White Paper highlights that there is no single correct scope, level of detail, or purpose for an EA. Different enterprises will expect their EA to guide change at different levels within the enterprise.

Herein lies a pair of substantive challenges. First, recognising that the range, scope, and scale of an EA are as broad as the scope and scale of enterprises and their change programs. Second, the ability to develop, use, and sustain the required EA will be equally as broad. Later in this Guide, various approaches to scope (strategy, portfolio, or project), the effort, and an approach to enhance the positive impact of EA are discussed.

The purpose of EA is to optimise the enterprise to realise a specific business strategy or mission.

All optimisation must be responsive to change. Optimising an enterprise to best realise the business strategy or mission requires all components to work together. Achieving competitive advantage is possible when all components are optimised to the enterprise strategy or mission.

An EA that highlights the relationship between the components of an enterprise helps facilitate effective management and exploitation opportunities. EA provides a strategic context for the evolution of the enterprise in response to the constantly changing needs of the business environment.

Furthermore, a good EA enables the sponsors and the enterprise as a whole to achieve the right balance across conflicting demands. Without the EA, it is highly unlikely that all the concerns and requirements will be considered and addressed with an appropriate trade-off.

Why use the TOGAF Standard as a framework for Enterprise Architecture?

The TOGAF Standard has been developed through the collaborative efforts of the whole community. Using the TOGA Standard results in Enterprise Architecture that is consistent, reflects the needs of stakeholders, employs best practice, and gives due consideration both to current requirements and the perceived future needs of the business.

Developing and sustaining an Enterprise Architecture is a technically complex process which involves many stakeholders and decision processes in the organisation. The TOGA Standard plays an important role in standardising and de-risks the architecture development process. The TOGA Standard provides a best practice framework for adding value, and enables the organisation to build workable and economic solutions which address their business issues and needs.

The TOGAF Standard value proposition is to enable organisations to operate in an efficient and effective way using a proven and recognised set of best practices, across the enterprise and in different sectors to address specific business and technology trends.

A key consideration is that guidance provided by the standard is intended to be adapted to address different needs and particular use-cases. That means it can be used to create a sustainable Enterprise Architecture for a broad range of use-cases, including agile enterprises and Digital Transformation.

TOGAF as EA Framework

The TOGAF Standard is a framework for identifying and implementing change, and provides:

- A definition and description of a standard cycle of change, used to plan, develop, implement, govern, change, and sustain an architecture for an enterprise; see the TOGAF Architecture Development Method (ADM)

- A definition and description of the building blocks in an enterprise used to deliver business services and information systems (see the TOGAF Content Framework)

- A set of guidelines, techniques, and advice to create and maintain an effective Enterprise Architecture and deliver change through new Solution Architectures at all levels of scale, pace, and detail

What Kind of Architecture Does the TOGA Standard Deal With?

There are four architecture domains that are commonly accepted as subsets of an overall

Enterprise Architecture, all of which the TOGAF Standard is designed to support:

- The Business Architecture defines the business strategy, governance, organization, and key business processes

- The Data Architecture describes the structure of an organization's logical and physical data assets and data management resources

- The Application Architecture provides a blueprint for the individual applications to be deployed, their interactions, and their relationships to the core business processes of the organization

- The Technology Architecture describes the digital architecture and the logical software and hardware infrastructure capabilities and standards that are required to support the deployment of business, data, and applications services. This includes digital services, Internet of Things (loT), social media infrastructure, cloud services, IT infrastructure, middleware, networks, communications, processing, standards, etc.

There are many other domains that could be defined by combining appropriate views of the Business, Data, Application, and Technology domains. For example:

- Information Architecture

- Risk and Security Architectures

- Digital Architecture

The TOGAF framework enables the creation of these multi-dimensional views and categorizes them to create specific domains that enable an enterprise to consider the wider scope of their enterprise and capabilities.

Architecture Abstraction

An architectural technique for dividing a problem area into smaller problem areas that are easier to model and therefore easier to solve.

Abstraction levels are layered in nature, moving from high-level models to more detailed models.

Architecture effort can be divided into four distinct abstraction levels that cross the Business, Data, Application, and Technology domains to answer fundamental questions about an architecture:

- Why -- why is the architecture needed?

- What - what functionality and other requirements need to be met by the architecture?

- How - how do we structure the functionality?

- With what - with what assets shall we implement this structure?

Enterprise Continuum

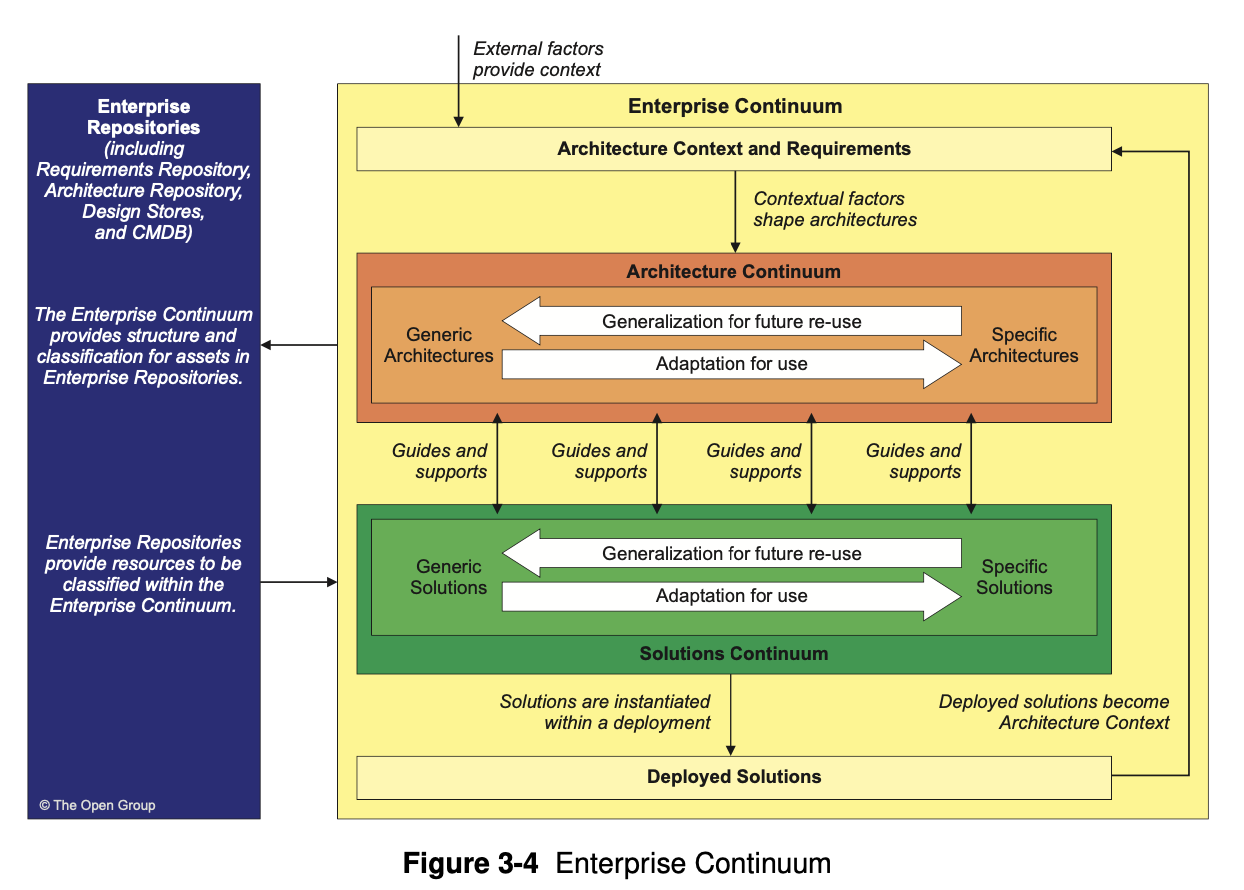

The TOGAF Standard includes the concept of the Enterprise Continuum, which sets the broader context for an architect and explains how generic solutions can be leveraged and specialized in order to support the requirements of an individual organization.

The Enterprise Continuum is a categorization for assets held in the Enterprise Repositories that provides methods for classifying assets, including architecture and solution artifacts as they evolve from generic Foundation Architectures to Organization-Specific Architectures. The Enterprise Continuum comprises two complementary concepts: the Architecture Continuum and the Solutions Continuum.

The Enterprise Continuum is described in detail in the TOGAF Standard - Architecture Content.

An overview of the structure and context for the Enterprise Continuum is shown in Figure 3-4.

Enterprise Continuum and Architecture Re-Use

The simplest way of thinking of the Enterprise Continuum is as a view of the repository of all the architecture assets. It can contain Architecture Descriptions, models, building blocks, patterns, architecture viewpoints, and other artifacts - that exist both within the enterprise and in the IT industry at large, which the enterprise considers to have available for the development of architectures for the enterprise.

Examples of internal architecture and solution artifacts are the deliverables of previous architecture work, which are available for re-use. Examples of external architecture and solution artifacts are the wide variety of industry reference models and architecture patterns that exist, and are continually emerging, including those that are highly generic (such as the TOGAF TRM); those specific to certain aspects of IT (such as a web services architecture, or a generic manageability architecture; those specific to certain types of information processing, such as e-Commerce, supply chain management, etc.; and those specific to certain vertical industries, such as the models generated by vertical consortia like the TM Forum (in the Telecommunications sector), ARTS (Retail), Energistics® (Petrotechnical), etc.

The Enterprise Architecture determines which architecture and solution artifacts an organization includes in its Architecture Repository. Re-use is a major consideration in this decision.

Architecture Repository

Supporting the Enterprise Continuum is the concept of an Architecture Repository which can be used to store different classes of architectural output at different levels of abstraction, created by the ADM. In this way, the TOGAF Standard facilitates understanding and co-operation between stakeholders and practitioners at different levels.

By means of the Enterprise Continuum and Architecture Repository, architects are encouraged to leverage all other relevant architectural resources and assets in developing an Organization- Specific Architecture. In this context, the TOGAF ADM can be regarded as describing a process lifecycle that operates at multiple levels within the organization, operating within a holistic governance framework and producing aligned outputs that reside in an Architecture Repository. The Enter pr ise Continuum provides a valuable context for understanding architectural models: it shows building blocks and their relationships to each other, and the constraints and requirements on a cycle of architecture development.

TOGAF Content Framework and Enterprise Metamodel

Overview

The TOGAF ADM provides lifecycle management to create and manage architectures within an enterprise. At each phase within the ADM, a discussion of inputs, outputs, and steps describes a number of architectural work products.

An essential task when establishing the enterprise-specific Enterprise Architecture Capability in the Preliminary Phase of the ADM is to define:

- A categorization framework to be used to structure the Architecture Descriptions, the work products used to express an architecture, and the collection of models that describe the architecture; this is referred to as the Content Framework

- An understanding of the types of entities within the enterprise and the relationships between them that need to be captured, stored, and analyzed in order to create the Architecture Description; this Enterprise Metamodel depicts this information in the form of a formal model

- The specific artifacts to be developed (see Section 3.6)

The Content Framework chosen is likely to be influenced by:

- The Architecture Framework selected as the basis for the Enterprise Architecture Capability

- The chosen software tool used to support the Enterprise Architecture Capability

Content Framework

The Content Framework defines a categorization framework to be used to describe the building blocks and artifacts reflecting decisions taken in creating the overall architecture deliverables.

The Architecture Repository, which is explained in Section 3.11, is structured to store the artifacts and work products identified in the Content Framework. The Content Framework is one element of the Enterprise-Specific Architecture Framework.

There are many alternative Content Frameworks (e.g., the TOGAF Content Framework, the Zachman Framework, DoDAF, NAF, etc.). Selecting a Content Framework is essential even though the choice of Content Framework is less important. The final Content Framework is usually adapted to fit specific organization needs.

Enterprise Metamodel

The TOGAF Standard encourages development of an Enterprise Metamodel, which defines the types of entity to appear in the models that describe the enterprise, together with the relationships between these entities.

For example, one type in an Enterprise Metamodel might be Role. Then the enterprise's Business Architecture models might include such instances of Role as Teller, Pilot, Manager, Volunteer, Customer, or Firefighter. Of course it would be an unusual enterprise that had all of these roles.

An Enterprise Metamodel provides value in several ways:

- It gives architects a starter set of the types of thing to investigate and to cover in their models

-

It provides a form of completeness-check for any architecture modelling language, or architecture metamodel, that is proposed for use in an enterprise

Namely, how completely does it handle the types of entity in the Enterprise Metamodel, and manage required facts about them such as their attributes and relationships? -

It can help ensure:

- Consistency

- Completeness

- Traceability

What Constitutes the Content Metamodel?

Regarding information management, the purpose defines what information the EA Capability must have at hand. In practical terms, information needs are derived from the viewpoint library and the information that supports the viewpoints. Consider what information is required to answer these two questions:

- How can the enterprise maximize the differentiation by aligning delivery of the portfolio?

- What should be done in response to one of the technology suppliers changing its product?

The Content Metamodel is used to structure architectural information in an orderly way so that it can be processed to meet stakeholder needs. The majority of architecture stakeholders do not actually need to know what the architecture Content Metamodel is and are only concerned with specific issues, such as: "How can the enterprise maximise differentiation by aligning delivery of the portfolio?"

The difficulty comes when, to answer this question, the EA Capability may need to answer:

- Which processes are orchestrated by the differentiating capability?

- Which processes require an application change?• What functionality does an application support

- What is the impact of using cloud infrastructure for the application on information security?

There are two approaches to defining the Content Metamodel. The most successful practice ensures that the central questions the EA Capability is established to address concern the focus.

In this case, look at the questions the EA Capability is established to answer, and identify the concerns and the viewpoints that address these concerns. The resulting viewpoint library defines the Content Metamodel. Anything more is noise and results in unnecessary work in future.

Following this approach leads to smaller information demands and crisply focuses the EA Capability on expected value. Any expansion in the range of critical questions the EA Capability is expected to answer will expand the information requirements. The majority of Enterprise Architects and analysts who have gone ahead to capture more information than what is required have consistently failed.

An alternative practice is to use an established Content Metamodel. This approach enables the EA Capability to address a broader set of questions. However, this approach typically leads to a great deal of superfluous model development and information management. One of the key pitfalls to avoid is assuming that an existing Content Framework is complete and will answer the questions the enterprise is asking of the EA Capability. If you undertake to use an established Content Metamodel, in order to minimise information management, identify the minimum information the EA Capability requires.

In either case, it is important to keep in mind that the information needed is infinite, and resources are finite. Minimise the information the EA Capability must maintain and focus on the purpose for which the EA Capability was formed. Address just those key questions. Take comfort in the fact that development of the Content Metamodel and viewpoint library will feed the evolution of each other.

Every component that is added to the enterprise's Content Metamodel comes with relationships that must be maintained and comes with attributes that must be tracked. The number of interim architecture states and options multiplies the amount of information that must be maintained. To succeed, the Leader should identify and define the absolute minimum information the EA Capability must maintain to deliver the stated purpose.

Recommendation from collective experience of The Open Group is that the Leader should start with the most likely set of questions from sponsors and stakeholders based upon the enterprise context and the purpose of the EA Capability to build the viewpoint library.

Explore the minimum information needed to answer the most pressing and recurrent questions.

When the questions appear to be hard to answer, refer to other models used in the enterprise like strategy development, operating model, business capability, process model, project management model, and systems development lifecycle model to validate whether they would provide the answers. Add only those additional reference models that are required to answer the new set of questions. As stated before, keep the scope limited to what is necessary and nothing more.

Consider what minimum information the EA Capability must have at hand, and what information it will need to gather upon demand. The information required at hand is the mandatory minimum. For the other information, ensure that there is a consistent way to gather and relate them to the mandatory minimum. This allows for traceability across more aspects of the enterprise.

The exercise is not to fill out all the information that might be needed in the future, but rather to identify the information that must be available to describe an EA to address the stakeholders questions. Test the kind of catalogs, matrices, and diagrams required to capture, analyse, and answer the questions asked of the EA Capability.

The TOGA Content Metamodel provides a good starting point for examining the information the EA Capability requires. It provides a list of common components and common possible relationships the EA Capability may want to keep track of (motivation, role, event, activity, location, resource, platform services) and a set of relationships. Explore the alternative Content Frameworks listed in Appendix A (Partial List of EA Content Frameworks). They are designed to address different purposes that may better align with the EA Capability's purpose.

To answer these stakeholder questions, the EA Capability will have to employ more than one technique and approach, to collate, classify, and represent back visually, verbally, and with appropriate context. To answer these questions requires an understanding and maintenance of capability, process, and application functionality models and a roadmap with appropriate intersections.

It is rare, but possible, to have a narrow scope for the EA Capability that leads to deployment of a narrow-domain approach like UML and BPMN or a pre-packaged Content Metamodel. Keep in mind that value questions supporting decision-making for strategy and portfolio require understanding cross-domain and multiple dimensions. They preclude use of narrow domain and pre-packaged metamodels.

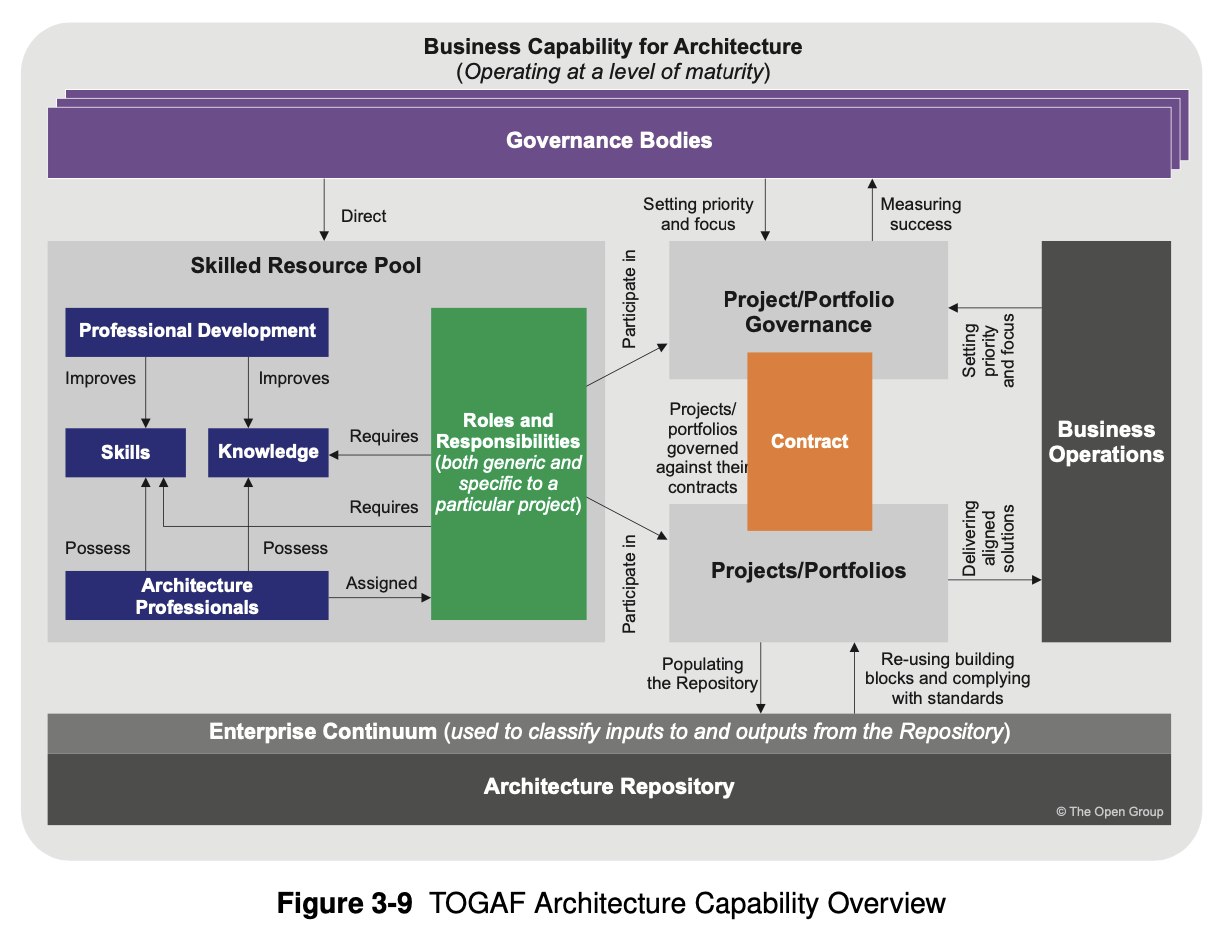

Establishing and Maintaining an Enterprise Architecture Capability

In order to carry out architectural activity effectively within an enterprise, it is necessary to put in place an appropriate business capability for architecture, through organisation structures, roles, responsibilities, skills, and processes. An overview of the TOGAF Architecture Capability is shown in Figure 3-9.

Establishing the Architecture Capability as an Operational Entity

Barring Architecture Capabilities set up to purely support change delivery programs, it is increasingly recognised that a successful Enterprise Architecture practice must sit on a firm operational footing. In effect, an Enterprise Architecture practice must be run like any other operational unit within a business; i.e., it should be treated like a business. To this end, and over and above the core processes defined within the ADM, an Enterprise Architecture practice should establish capabilities in the following areas:

- Financial Management

- Performance Management

- Service Management

- Risk and Opportunity Management (see Section B.34)

- Resource Management

- Communications and Stakeholder Management (see Section 4.36)

- Quality Management

- Supplier Management (see Section B.40)

- Configuration Management (see Section B.7)

- Environment Management

Central to the notion of operating an ongoing architecture is the execution of well-defined and effective governance, whereby all architecturally significant activity is controlled and aligned within a single framework.

What is an EA Capability and EA?

In short, an EA Capability is the ability to develop, use, and sustain the architecture of a particular enterprise, and use the architecture to govern change.

This Guide discusses establishing and evolving an EA Capability; it explicitly does not discuss an EA department or any other organizational element. The term Capability is often defined tortuously, most commonly when it is used as part of a formal analysis technique when definition must be precise and constrained. This Guide uses EA Capability as a management concept that facilitates planning improvements in the ability to do something that leads to enhanced outcomes enabled by the Capability.

In its simplest terms, EA is used to describe the future state of an enterprise to guide the change to reach the future state. The description of the future state enables key people to understand what must be in their enterprise to meet the enterprise's goals, objective, mission, and vision in the context within which the enterprise operates. The gap between the enterprise's current state and future state guides what must change within the enterprise.

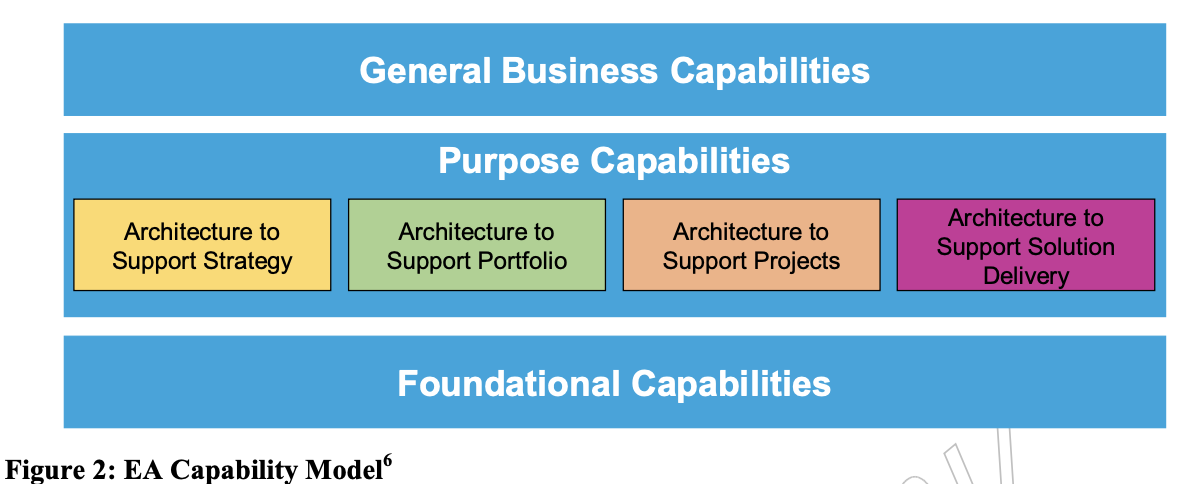

Using the capability model in the World-Class Enterprise Architecture White Paper2 as a base, we assume that an EA Capability is established specifically to support one or more purposes.

Typically, there are four broad purposes of an EA Capability:

1. EA to support Strategy: deliver EA to provide a target architecture, and develop roadmaps of change over a three to ten-year period

An architecture for this purpose will typically span many change programs or portfolios.

In this context, architecture is used to identify change initiatives and supporting portfolio and programs. Set terms of reference, identify synergies, and govern execution of strategy via portfolio and programs.

2. EA to support Portfolio: deliver EA to support cross-functional, multi-phase, and multi-project change initiatives

An architecture for this purpose will typically span a single portfolio. In this context, architecture is used to identify projects, and set their terms of reference, align their approaches, identify synergies, and govern their execution of projects.

3. EA to support Project: deliver EA to support the enterprise's project delivery method

An architecture for this purpose will typically span a single project. In this context, the architecture is used to clarify the purpose and value of the project, identify requirements to address synergy and future dependency, assure compliance with architectural governance, and to support integration and alignment between projects.

4. EA to support Solution Delivery: deliver EA that is used to support the solution deployment3

An architecture for this purpose will typically be a single project or a significant part of it.

In this context the architecture is used to define how the change will be designed and delivered, identify constraints, controls and architecture requirements to the design, and finally, act as a governance framework for change.

What is Expected of an EA Capability?

Where will the EA Capability team be engaged? How to validate that the EA Capability is doing the right thing?

A quick perusal of the literature on the role of an Enterprise Architect or EA Capability will leave no understanding of the role. At the extremes, the role is classified as an enabler of enterprise transformation or responsible for the selection of technical IT standards. This wide variance is responsible for most failures of an EA Capability. A mixed bag of expectations will result in improper scoping for work products and planning the evolution and development of the EA Capability.

In its simplest terms, EA is used to describe the future state of an enterprise to guide the change to reach the future state. The description of the future state enables key people to understand what must be in their enterprise to meet the enterprise's goals, objective, mission, and vision in the context within which the enterprise operates.

The gap between the enterprise's current state and future state highlights what must change within the enterprise. This gap is a function of the enterprise context and the scope of changes the enterprise sees.

Introduction to Risk Management

There will always be risk with any architecture/business transformation effort. It is important to identify, classify, and mitigate these risks before starting so that they can be tracked throughout the transformation effort.

Mitigation is an ongoing effort and often the risk triggers may be outside the scope of the transformation planners (e.g., merger, acquisition) so planners must monitor the transformation context constantly.

It is also important to note that the Enterprise Architect may identify the risks and mitigate certain ones, but it is within the governance framework that risks have to be first accepted and then managed.

There are two levels of risk that should be considered, namely:

- Initial Level of Risk: risk categorisation prior to determining and implementing mitigating actions

- Residual Level of Risk: risk categorisation after implementation of mitigating actions if any)

The process for risk management is described in the following sections and consists of the following activities:

- Risk classification

- Risk identification

- Initial risk assessment

- Risk mitigation and residual risk assessment

- Risk monitoring

Definition of Risk

Risk is the "effect of uncertainty on objectives" (ISO 31000:2009 [6]).

The effect of uncertainty is any deviation from what is expected – positive and negative.

Understanding the term "risk" is central to understanding the broader concepts of ERM, and the role of effective Enterprise Architecture and Enterprise Security Architecture. In this Guide we define risk in line with ISO 31000:2009. Risk is the effect that uncertainty has on the achievement of business objectives. The uncertainty is concerned with predicting future outcomes, given the limited amount of information available when making a business decision.

This information can never be perfect, although our expectation is that given better quality information we can make better quality decisions. Every decision is based on assessing the balance between potential opportunities and threats, the likelihood of beneficial outcomes versus damaging outcomes, the magnitude of these potential positive or negative events, and the likelihood associated with each identified outcome. Identifying and assessing these factors is known as "risk assessment" or "risk analysis". "Risk management is the art and science of applying these concepts in the decision-making process. Risk can be seen at the strategic long-term level (overall direction of the business), the medium term tactical level (transformation projects and programs), and at the operational level (regular day-to-day operational decisions, processes, and practices). The objective of risk management is to optimise business outcomes to maximise business value and minimise business losses. Risk can be seen at any level in the business stack (see Figure 2), but is always driven top-down from assessment of business value and its optimisation.

Uncertainty typically involves a deficiency of information and leads to inadequate or incomplete knowledge or understanding. In the context of risk management, uncertainty exists whenever the knowledge or understanding of an event, consequence, or likelihood is inadequate or incomplete.

This balanced view of risk is also embedded in SABSA, including the enabling of benefits arising from opportunities as well as the control of the effects of threats. Arguably, the sole role of the Enterprise Architect is to create an operational environment in which operational risk can be optimised for maximum business benefit and minimum business loss.

Operational risk is concerned with the threats and opportunities arising in business operations. SABSA is an architectural and operational framework for reaching out to opportunities and enabling positive outcomes to attain defined business targets and managing negative outcomes of loss events to within an enterprise's tolerance towards risk - namely their risk appetite.

Introduction to Gap Analysis

A key step in validating an architecture is to consider what may have been forgotten. The architecture must support all of the essential information processing needs of the organisation.

The most critical source of gaps that should be considered is stakeholder concerns that have not been addressed in prior architectural work.

Potential sources of gaps include:

- Business domain gaps:

- People gaps (e.g., cross-training requirements)

- Process gaps (e.g., process inefficiencies)

- Tools gaps (e.g., duplicate or missing tool functionality)

- Information gaps

- Measurement gaps

- Financial gaps

- Facilities gaps (buildings, office space, etc.)

- Data domain gaps:

- Data not of sufficient currency

- Data not located where it is needed

- Not the data that is needed

- Data not available when needed

- Data not created

- Data not consumed

- Data relationship gaps

- Applications impacted, eliminated, or created

- Technologies impacted, eliminated, or created

Long-Term Compliance Reporting

The chapters discussing walk-throughs for Architecture to Support Strategy, Portfolio, and Project all included assessments of in-flight change and consider using summary reporting with a high visual impact. Below is an example of reporting against constraints, expected value, and known gaps. In all cases, the assessment will return either not applicable, conformance, or non- conformance. Good Practitioners will look for binary tests: compliance and con-compliance (Red/Green) where possible. Where binary testing is not possible, a 1-to-3 scale (Red/Yellow/Green) should provide sufficient range to provide a summary report.

-

A common trap is getting into efforts to fix terminology by using a different synonym. This is always done when people have added meaning, or special conditions, to a word. Implementation means “the process of putting a decision or plan into effect”. Feel free to substitute transformation, change, program execution, or deployment if these words align with your preferences. ↩